Sexual violence is discussed in this episode. Reader and listener discretion advised.

In Western films, rape victims are often either vengeful or vegetative.

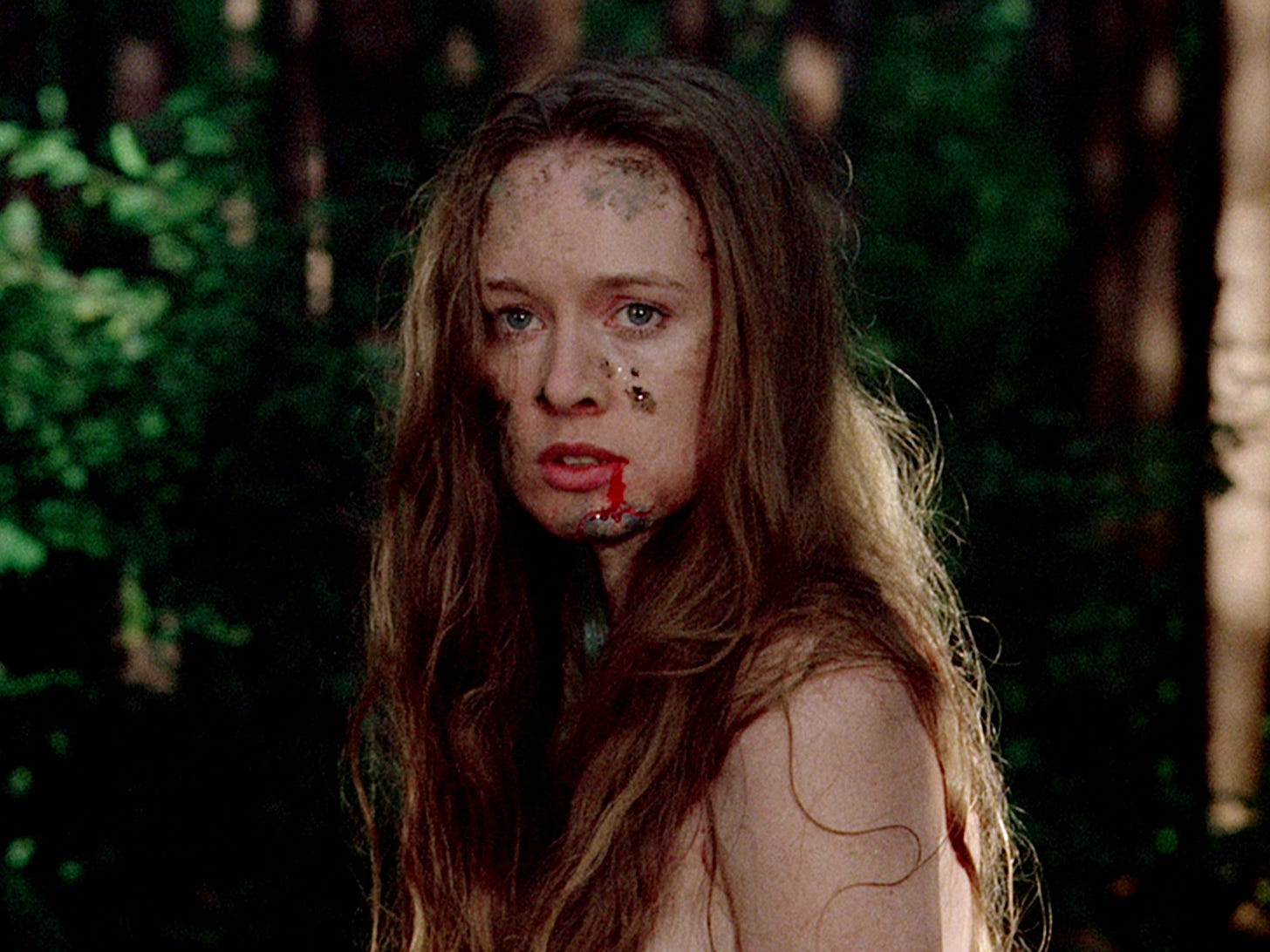

Savage Streets paralyzes Linnea Quigley’s character to make way for Linda Blair’s righteous kills. I Spit On Your Grave elevates its central survivor’s agony to mythical proportions, an approach taken by later films such as Revenge. Don’t Breathe and Barbarian use sexual violence as both plot device and gross-out shock effect that incapacitates or transforms victims; Saint Maud and Promising Young Woman both lay out two very different but ultimately self-destructive ends of the act itself. Varda also indulges in this misery with Vagabond, as it’s part of a larger tragedy that culminates in her heroine’s demise, even if the director manages to instill a larger sense of resilience and grit in her.

But then — maybe we can blame this all on The Virgin Spring… or is that Last House On The Left?

It should be noted — the films mentioned above are good, well-made, and commendably executed pictures worth watching. I Spit On Your Grave and its many sequels, particularly, are cathartic and vital watches for any survivor — or anyone who likes to watch rapists get gored. While there are nuances here, though, there is a general sentiment about rape that can be sussed out from just these ten films mentioned. Survivors of assault fall into two categories: victims and avengers. Those who survive rape, and those who punish rape. Perhaps the only film I can think of that truly complicates this narrative is Deliverance, but only just.

Imagine, then, describing the plot of Nikkatsu’s 1976 Roman Porno feature, Rape!, to any well-adjusted Western viewer. Director Yasuheru Hasebe’s central librarian Natsuko (Natsuko Yashiro) is raped in an elevator near the outset of the film. After she confides in a friend at work, the friend simply brushes her off — doesn’t she know this happens to every woman? In fact, she should learn to enjoy it. Curious if her friend is right, Natsuko puts herself into riskier and riskier situations just to see what will happen to her. When the worst does happen, she finds herself besting prospective men by sleeping with them.

Then Natsuko realizes — what she’s really craving is sexual release from the truck driver who attacked her in the elevator (played by Keizo Kanie.)

Rape!, undoubtedly, would ruin the minds of some. To an audience conditioned by aforementioned depictions of sexual assault, the softcore pornographic interpretations here are offensive. That’s to say nothing of the central narrative, which — taken in bad faith — can be reduced to, “women like being raped, actually.” But there is more to Hasebe’s film and writer Seiji Matsuoka’s script than this ultimately reductive read. Instead, both creatives try to navigate the complicated realities of sexual violence in contemporary Japan and display a genuine, uncanny empathy with the headspace of assault survivors.

It’s in the minutiae — moment to moment interactions Natsuko has with other women that leave her alienated, lost, confused with how to process her emotions. The film lets her pain sink in as she re-acclimates to the workforce and tries to pretend things are still the same. Feeding herself, talking with friends, and going out by herself are all different now. Yet to acknowledge this difference is to stand out, and in a work culture built around productivity, hegemony, and uniformity, standing out is as taboo as the act of rape itself. So Natsuko internalizes and compounds her own trauma until she understands and makes peace with it as a kink.

There’s not a moment where I believe Hasebe nor Matsuoka find this to be a positive development. Instead, their picture seems as horrified at this concept as the prospective viewer is. Pink films are a diverse lot, and even within the canon of Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno output, there’s a broad range of genres, tones, and styles at play. I say this to emphasize — it’s clear when a project is more irreverent towards its subject matter and when it’s not. For instance, the Angel Guts films — specifically Red Classroom and Nami — eroticize assault while also relying on horror imagery to sell a dramatic shock factor. Meanwhile, even extra-demented pictures like Woman In The Box will use comedy to find strange, perverse silver linings in grim scenarios. Then there are even funnier ones, like middling but amusing I Love It From Behind.

Point being, there’s comedy in pink film, and comedy in Roman Porno, but Rape! is the furthest thing from funny. (As tends to be the case.)

Stylistic cues point to giallo influence, which helps drive home the psychological peril and horror of some sequences. Bava is the primary point of reference here it seems, as much of the shadowy, claustrophobic mise en scene recalls his ‘60s and ‘70s work — complete with black gloves — but there’s also a bit of Martino in here as well. Giallo is of a pair with Rape! as well, as many films from that Italian movement trade in similarly complicated, occasionally permissive perspectives of sexual violence — such as Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion (1970) and All The Colors Of The Dark (1972.) Both films center women enacted upon and put through sexual peril that they — through some form or another — come to enjoy in some capacity.

Is art such as this apologia? From a hegemonic Western feminist understanding of sex and gender, absolutely. But both these Japanese and Italian movements can often suggest that there is more to enduring, surviving, and overcoming sexual violence than retributive violence, endless grief, or death. Perhaps someone is raped, and the only way they can find pleasure once they feel safe enough again is controlled force and aggression. Or perhaps a character is raped, but they mainly have to worry about picking up groceries and getting to work on time because nobody cares. This is a level of nuance to surviving assault that is often avoided, simply because it isn’t glamorous. It doesn’t feel good to watch this happen. In fact, it makes us feel uncomfortable, because we know that what we’re watching is deeply wrong.

This is the point.

Rape! captures the very true pain of trying to reintegrate into society after you’ve been raped. Survivors often don’t know how to process their pain, once they’re told they can’t feel it. So it manifests in inconvenient, ugly ways that have troubling consequences for all involved. Trauma can look like abusive relationships, risk-seeking behavior, self-harm, substance abuse, or any and all of the above. Making the same mistakes and hating yourself for it. Not being able to see red flags until it’s too late. There’s no one way to be traumatized by rape. However, it most often does not result in vegetation or righteous fury. Most of the time? It looks like Natsuko here — confused, enraged, aroused, desperate to feel anything worse than what she has to carry around. Even her final gambit has predictably tragic consequences, albeit unexpected ones. Being faced with her rapist and putting him right where she wants him isn’t enough. It doesn’t fix what has been done. Nothing can.

Because Rape! isn’t just about Natsuko being raped. It’s about rape as a construct, a power structure, an act that is done in presumed submission of the victim. When someone has had their worth and personhood devalued so utterly, there’s a feeling that their actions carry no consequence and their goals have no meaning.

Yet most of us are forced to carry on, as we can’t simply bleed our pain out as words, song, paint. That’s not enough to survive under capitalism without relying on constant charity. And so most of us must accept that the apparatus of rape exists, that it has ensnared us before (perhaps multiple times, for some of us,) but that it will never truly go away. Rape as an act of primal brutality is a choice, a choice certain creatures have always made and all have dominated with. America, Asia, Europe — all built from the innards of violated indigenous populi and other martyred non-believers.

What, then, is the most effective anti-rape art? Most rapists wouldn’t consider themselves rapists, after all, with how many cultural inevitables are signposted when it comes to sex. Films like Rape! are a good way to convey the pride and power inherent to the rapist mindset — a sense of entitlement that comes with the act itself. For the rapist there is often no question about what they’re doing, as if there was, there would be hesitation and the rape would not be occurring.

Once a rapist commits to the act, they believe in an inherent righteousness to their conquest. Israeli troops who rape Palestinians civilians, for instance, don’t think of Palestinians as human. Nor did white slave owners view their slaves as more than property. And neither did any partner who was told - begged - stop, only to push forward because you can’t rape somebody you’re dating — right? This is a toxic, evil mentality, and one that’s captured well. How little consequence or care these men have for the women they hurt and lust after is horrific in its own right.

There is some catharsis, however, to be found in how Natsuko compartmentalizes her assault. It’s inconvenient to acknowledge that rape victims can and do fantasize about rape, but we must. Because there must be some room in our culture to discuss and delineate between fantasy and reality. There must also be room for survivors to feel safe enough in their vulnerability to share and live out these fantasies. In exploring hardcore, rape-focused pornography and engaging in BDSM play with my partner, I’ve found a level of peace with my CSA and adult SA traumas that therapy and grief can’t access. In Rape!, Natsuko hopes that her dangerous fantasy being made reality will bring about her own peace. That is her mistake — and that is the point to the film’s existence.

Because in filming, editing, and distributing a 71-minute softcore erotic drama set to cool jazz called Rape!, the filmmakers have given credence to and acknowledged this inconvenient trauma. They have provided viewers such as myself a safe vector to feel these feelings, a place to work out our intrusive thoughts and scry their potential consequences — good, bad, in-between. Along the way, they have empowered and not disenfranchised their lead actress, as Nikkatsu actresses tended to speak highly of their time working on the films. This is a far cry from the violation of something like Bertolucci’s Last Tango In Paris, which inflicted real-life trauma on Maria Schneider to make ugly suggestions about sex and power. It, too, speaks to a higher regard for women’s complexity and autonomy than some of Hasebe’s Western auteur contemporaries — such as Sam Peckinpah, for example.

It’s frustrating to be faced with a larger unwillingness to see Roman Porno as much beyond “weird” or “scary” movies from Japan. Discussing many of these films is social suicide, as some of the topics alone are phrases an average person may have muted on social media platforms. Outside of a few stand-outs, the Letterboxd entries for most of the Roman Porno entries remain distressingly low because there are distressingly few in English. Further, even a few proponents of the Roman Porno pictures — and pink film in general — can engage in reductive discourse or willful misunderstanding of the genre, typically based in a facile appreciation of novelty and shock value.

How, then, does one lobby for the critical evaluation of Rape! in the West? It starts by challenging the limits of how sexual assault is depicted in film. By suggesting after we are taken advantage of as small children, or after we are violated in private as adults, that there is more left for us than violence and pain.

That the scary desires which spring from those moments wrested from our hands are not wrong, but something to be dealt with responsibly by people who care about you.

And that — above all — we can, should, and must continue to depict rape in film. As a crime of passion, a war crime, an act of violence, any and every reason.

If I can suggest these things, and you can consider them, then perhaps we can chat about Rape! one day.

If you’d like to learn more about the history, production, and controversial reception of I Spit On Your Grave, be sure to listen to my Cinema Cauldron episode on those very things.

Share this post