The Goddess is a 1958 film directed by John Cromwell and written by Paddy Chayefsky. Released during the zenith of Marilyn Monroe’s tabloid troubles, the film paints an unflattering portrait of an ignorant Southern girl who goes blonde and strikes it big in Hollywood. Marketed as “the disrobing of a generation,” the film is an ugly and mean-spirited attack on no

t only Monroe, but of women like her. Chayefsky relies on Freudian logic to diagnose disgraced heroine “Emily” (played by Kim Stanley) as unhappy due to her lack of fulfillment as a mother, and ultimately dooms her as too mentally fragile to fulfill her biological duty by film’s end.

This sort of narrative played into both left-wing and right-wing social politics of the time. However, it must be noted that establishment liberal thought leaders took deep stock in Freud and the teachings of his nephew, Edward Bernays. Further, Freud’s daughter Anna rose to status in the ‘40s and ‘50s as the leading voice of a growing psychotherapy movement across America. Psychotherapy not only gave Americans the tools to unlock their desires, but it also enabled political establishments and corporate entities to condition post-war minds through sublimation.

For more on this, I’d highly recommend the Adam Curtis documentary Century of the Self. It provides a radical re-contextualization to our hegemonic narrative of American history.

As this pertained to The Goddess, then, a contemporary audience would be clued into the plot-based morality that guides the film. In an era where eggs were added to Betty Crocker recipes because it created a psychological link between brownie mix and baby batter, it cast a grim portent on Monroe, Mansfield, and any other “loose” woman. Chayefsky’s picture had a simple answer, emboldened by the very real and very dangerous psychological movement that had grasped America’s consciousness by that point. An irony is that noted Zionist Chayefsky himself was reportedly an absent, neglectful, and angry husband — we could consider this a sort of Freudian projection in and of itself.

In the four years that followed The Goddess, Marilyn Monroe became a close follower of Anna Freud, whose advice she already held in high esteem from published writings and newsletters. Monroe sought the help of Ralph Greenson, a devout follower of Freud’s, and began what should have been restorative psychotherapy. Monroe and Greenson lived next to each other in houses that were almost identical in style and architecture, as Greenson invited the actress into his own family and treated her as if she belonged. This was meant to cure the actress’ deep-seated dissatisfaction about her lack of a stable, comfortable home life and — ultimately — stabilize the troubled actress.

It had the opposite effect. Monroe felt increasingly isolated as Greenson and others tried to diagnose and “cure” her to no avail. Greenson noted to Anna Freud in a letter that Monroe seemed beyond help because something was — ostensibly — too vacant and too empty on a core level.

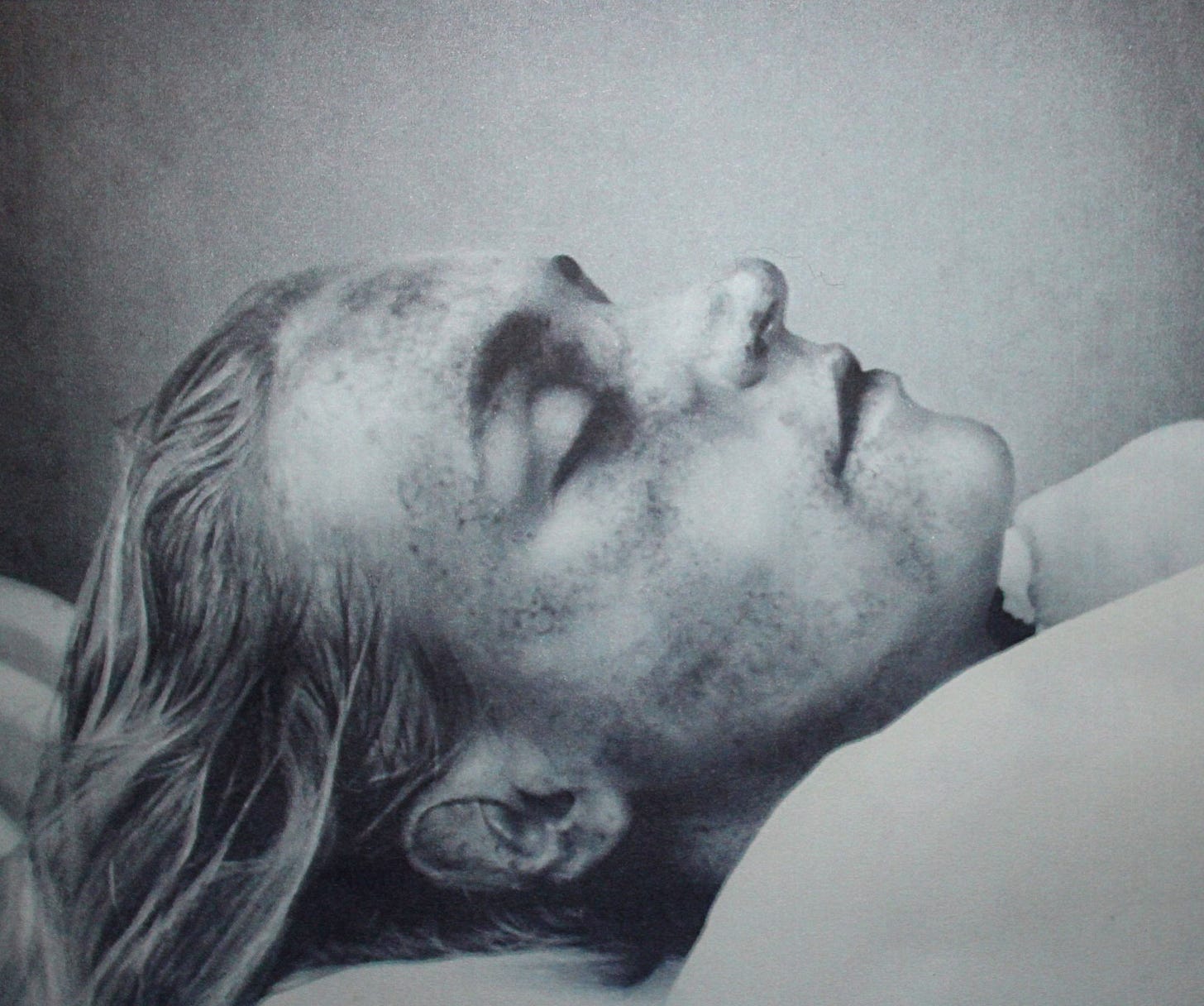

On August 5th, 1962, Greenson broke into her home after housekeeper Eunice Murray noticed a light on in the dead of night. Marilyn Monroe was naked, face down on the bed. Her hand was clutching the telephone receiver in a vice, and her body enmeshed in the sheets — as if she’d writhed, struggled, and ultimately failed to call for help. Empty barbibituate bottles were scattered around the room.

At 3:50 AM, Marilyn Monroe was legally declared dead by overdose at 36.

It is difficult to not think of Marilyn Monroe when watching Ti West’s X series. The neon-slicked, sun-soaked third entry, MaXXXine, has finally hit American theaters and brought Mia Goth’s psychosexual journey to an end — for now. With the film’s release, however, has come something of a mixed and muted response, especially compared to the hyperbolic level of praise heaped on the initial two entries. Perhaps this is due, in part, to the fact that I am completely disconnected from X, TikTok, or any other social media that is not BlueSky or Letterboxd. But even with those considerations, the level of viral marketing and physical promotion for MaXXXine simply has not hit the fever pitch of the first two.

(The box office is fine, but Inside Out 2 and The Garfield Movie have dominated the mindshare.)

MaXXXine invokes the spirit of Monroe in the ambition of its titular lead. Maxine is a homespun entrepreneur, a creator of her own narrative and mistress of her own destiny. In two films, sets of men and women attempt to pigeonhole and define her; in both, the appraisals fail as Maxine is the only one left standing. As the world insists that it has her figured out, Maxine struggles to figure herself out amid mounting pressure to go legit in the acting world.

Of course, Richard Ramirez and a quasi-satanic cult stalking the hot Los Angeles nights don’t help matters. Maxine fights to hold onto a role in auteur Elizabeth Bender’s gory horror sequel The Puritan 2 (1985,) as she works peep show booths and watches as her friends get systematically targeted and slaughtered. Police officers hound her, protestors antagonize her profession, but Maxine simply keeps her head down and working on her dream. Unfortunately, dreams often emerge from our hazy pasts, and soon Maxine’s own threatens to destroy the glistening future she envisions. Only the nastiness and tenacity learned from her survival may be enough to hang on.

Goth serves up an unexpected performance here. The actress — known for her exuberant, eclectic, and frequently absurd turns — gives audience her most subtle and subdued role yet. (Even against the likes of Emma.) Pain and grief has caught up with the character, as Goth mumbles and glares through scenes — emotionalism saved for the camera or herself. There are shades of complexity to Maxine here that I wasn’t aware existed in the first film, and perhaps they didn’t. Goth’s performance invites an examination of not just capital-t “trauma,” but how the specific ill of wanting to succeed in America slowly erodes at and eventually breaks one’s psyche.

Functionally, MaXXXine is a straightforward thriller with occasional traipses into broad satire and flirtations with surrealism. The kinetic momentum of the picture is defined by loud, explosive punches of sonic and aesthetic intensity. Maximalist filmmaking of the 1980s is king here, with filmcraft that evokes Mann’s larger-than-life coolness or Ferrera’s sun-flicked neo-noir endemic of their period work. It is a prettier, more produced picture than even higher-budgeted examples of horror and exploitation from the era. In that sense, West and his crew evoke a collective memory of the ‘80s in order to probe the seedier bits.

While this approach works, it does at times come across as pandering and obvious. The score is functional, and serves the basic purpose of hitting the high notes of pretty sleaze without feeling cheesy or phoned-in. But the licensed music on tap is embarrass, a grab bag of needle drops from I Love The ‘80s or Now! That’s What I Call ‘80s playlists. I understand the utility of taking actively bad pop music and using it to illustrate how dire the Top 40 really was in 1985. Some drops — like “Welcome to the Pleasuredome” and “Shellshock” — are interesting, and I’ll never complain about a Mary Jane Girls pick. But “Bette Davis Eyes, “Gimme All Your Lovin,” fucking “Man In Motion” — these are tired choices that only elicited empathy and eye rolls from me.

Other bits of period storytelling also trip on their own understanding and depiction of the era. Elizabeth Bender is an audacious nod to cult horror figure Suzanna Love — actress Elizabeth Debicki dons Love’s glasses from Olivia (1983) and her hair from The Devonsville Terror (1983.) As if tacit confirmation, the first Puritan installment is said to have been released two years prior. Both films are clear influences here, as is the transgressive and radical contributions of Suzanna Love. To her credit, Debicki turns in one of the best performances, grounding it through steely command and domination versus leaning into the broader approaches adopted by Goth, Kevin Bacon, and Giancarlo Esposito. Even as the script betrays her, the actress ensures that the director stands out in an over-the-top film — not an easy task.

In the narrative of MaXXXine, Bender is used for a red herring much in the way a giallo misleads its audience with obvious “clues.” She occupies a flirtatious space with Maxine, akin to Susan Scott’s role in Le Foto Proibite Di Una Signora Per Bene (1970) spliced with the controlling director of Argento’s Opera (1987.) The latter is an important film to bring up, as much of the loopy and paranoid cinematography there is evoked here — as is the contemporary litigation of violent media.

But Debicki’s character is a somewhat reductive caricature of ambitious women of the era. There is a duality of admiration and contempt held for Bender, one that shades any scene she shares with Maxine. Her serious efforts at “A ideas” and her tight control over horror sets is almost framed as needless and pretentious. The level of control she seeks should be juxtaposed with Wayne Gilroy in X, a character who is treated with markedly more seriousness and sympathy. Gilroy’s reductive, essentialist worldview is ultimately framed as transgressive and proto-feminist within the context of the series; meanwhile, Bender is pigeonholed as an over-serious and pretentious killjoy who might also be a lesbian serial killer.

In our post-post-modern age of irony-poisoned reads of contemporary cinema, it’s easy to embrace a character like this as a cool “bad girl” type. But what it’s actually doing is an unconscious, careless resurrection of tropes that actually serve to keep current social orders in check. A leering, threatening femme of ambiguous gender presentation is framed as frivolous and perhaps overly ambitious, yet the film relishes giving her control for cheap “girl boss” points that couldn’t be at the era. The fact that Suzanne Love’s success was primarily under Uli Lommell, and credit not fully given until later, is not reckoned with by this pantomime.

Worse, it could be said that this type of historical revisionism astroturfs an era of the horror industry to make it seem less sexist and less exploitative than it could actually be. Slumber Party Massacre — one of the few slashers of the era directed and written by women — had much of its feminist satire pared down and Roger Corman’s mandatory nudity requirement fulfilled. While this is not a puritanical takedown of the lurid elements of horror — the genre wouldn’t exist without them — it is a caution to not falsify history and make an industry look better for women than it historically has been.

Fortunately, other elements of the film hold up better and tease out more sumptuous themes. MaXXXine’s most effective elements involve the heroine’s hateful relationship with her evangelical father. The script invites parallels between his zealotry and the uncanny drive Maxine possesses, which itself juxtaposes American religious fanaticism with the destructive allure of Hollywood. Viewers are invited to consider fame not as a goal, but as a place one arrives at after enough sacrifice and loss. The most emotive, raw, authentic performances can often come from the most broken people, and the system itself benefits from breaking those people down further. Shelley Duvall and Linda Blair alike were deliberately terrorized by their directors, because — to the director — the best way to ensure the film was scary is convincing the audience that the woman or girl is actually scared. Both were then othered and ostracized by a system that relished their destruction and panic, then immortalized as “scream queens” — women who looked good scared.

Shelly Duvall lived in seclusion after being wrongfully put under a national spotlight by Dr. Phil. Thankfully, dedicated fans and friends helped make her remaining years much more pleasant. Meanwhile, Linda Blair has spent years helping animals and mostly avoids talking about The Exorcist. Both have had highly publicized bouts with tabloids desperate to pin them as crazy or broken. Neither are true, but the perception remains. And it traces back to the inclination to terrorize women, film it, and show that fear to the masses in order to capitalize on it and influence social order.

MaXXXine actually grapples with this, somewhat. West undoes an archetypal myth — the doe-eyed, virginal final girl whose own hapless survival often feels accidental. Here, Maxine is a nasty, spiteful, violent person. She dresses in plain jeans and tees, only getting glammed up when the work calls for it. The aspiring actress carries a gun, turns her nose up at protestors, and doesn’t get involved with cops because she doesn’t want the powers that be sticking their noses in her business. At her heart, Maxine is a deeply conservative woman whose very existence is a right-wing power fantasy. Of course, I think this by design. One does not draft three films centered around religious puritanism and sexual liberation, then arrive at a character like this by accident.

Why I actually love this choice is that — above all — it’s honest. At the turn of the ‘80s, young voters turned to Reagan to solve problems. Reagan, however, was really giving a false bill of sale to the American people. His campaign relied on misinformation to an almost comical degree — routinely using polls and focus groups to find out what America’s youth wanted to hear, then telling it to them. The strategy worked, and in that era, an entire new generation of neo-cons were born. A contingent of young voter who viewed themselves as scrappy, hard-working, and in pursuit of striking it big. The president’s administration promised equitable pay for those who worked hard, while attacking “welfare queens” in the years leading up to his presidential campaign.

These values are embodied in Maxine, yet MaXXXine — as a picture — does not frame this as a good nor bad thing. In that sense, it’s a departure from American cinema in that it isn’t explicitly trying to have a “message” in one way or another. Ultimately, we are forced to sit with Maxine as our perspective character, with her ignorant, funny, and ultimately likable guttersnipe demeanor carrying the weight of the picture on her shoulders. Instead of going bigger, bawdier, nastier, Goth actually exercises restraint. She’s quieter and more contemplative than the first two pictures, and certainly more cautious than her gonzo performance in Infinity Pool (2023.) If anything, her surly growls and demure requests ground Maxine amid a rogue’s gallery of absurd caricatures and vilification.

But if we are to take Maxine as a conservative archetype in earnest, I don’t think this undermines the core integrity of the picture. What many Americans are unwilling to admit is that our country and its politics are inherently right-wing, and have been since the beginning. Our cultural “left” continually moves rightward not because things are getting worse — they are, sure — but because it’s become more and more transparent that we are trapped in a system designed for us over a century ago. Contemporary ills are largely results of violent pre-fab industrialism and corporate psychological warfare that have come home to roost because more people can arm themselves with information against it. We are not in control, but we are more aware than ever how true that is.

Through the prism of MaXXXine and its titular lead, then, Ti West makes the acerbic observation that perhaps becoming the embodiment of America’s ills is the only way to truly survive it. In that sense, Maxine occupies the space of Ginger Rogers, Lucille Ball, and Doris Day — women typified by their strong public images and staunch conservative politics. Meanwhile, the deaths of Judy Garland and Marilyn Monroe — two left-leaning women who could never “belong” in our culture — hang heavy over the trilogy, too. In Pearl, we see the starry-eyed hope of success during cinema’s golden age harshly held up to the material realities of the era — Oz references aplenty. When Pearl can’t succeed, she rots and takes her aggression out on a low-budget porn actress with more to lose than her in X. But Pearl’s own misery drains the joy and passion from the actress’ work, and once she finally “makes it,” Maxine has to hide her fear, her violence, her avarice behind a steely but mumbling demeanor.

Beneath the surface lurks a phrase ingrained in Maxine by her father — “I will not accept a life I do not deserve.” At the outset and during a few key points of the film, we see this being forcibly drilled into her on-camera. While this phrase has been a call to action for her, and while certain fans have taken it as a personal credo (yuck,) the fallacy of this belief is laid bare here. Her guiding ethics have been instilled in her by a hateful, ugly man whose mistreatment and shame of his own daughter pushed her away. Yet this early experience of filming Maxine and forcing her to do something left an indelible impact on the woman’s life. Her worst shame and her greatest drive come from the same place, the same man.

This is a powerful and knowing desiccation of Freudian social politics as they pertain to the American family. Maxine is a product of both her father’s loins and his ideologies. Her guiding ethos was drilled into her by force, yet Maxine has reclaimed it as empowerment and liberation. But where MaXXXine stops short of becoming another entry in the growing “good for her” canon is that her liberation comes with a cost. In order to succeed and navigate the life she’d scraped together for herself, Maxine must reverberate the echo of every violent and controlling impulse instilled in her by American society. In other words, the heinous circumstances created for women by men is a power that Maxine must wield lest it breaks her. Her vulnerability, fear, doubt must be sealed behind a veneer of gratitude and piousness. To kill God, the father, the masculine, the power that shackles her, Maxine must use her pain to free herself.

Of course, it’s all accomplished within the limits of faux maximalism at its guiltiest, glitzed up by a liberal assortment of aesthetic and narrative giallo tropes. Ti West plays it fast and loose with social ills, arriving at the sort of conclusions one might expect a horror community figure to have in 2024. Dee Snyder’s Senate hearing is treated like vital protest text, the Christian Right is stereotyped into an easily digestible figurehead, period horror is referenced via name, date, and actor, and — naturally — the cute nerd who works at the video store is cool and not like other guys. It’s a conception of the ‘80s that 50-somethings in Transformers or Fright Rags shirts could agree with uncritically, in other words.

This sort of art, though, has its limits. Recent films like Censor (2021) and Revealer (2022) have played in similar territory as West does here, but to a much more affecting degree. Censor, for example, stoked the flames of moral puritanism of ‘80s anti-horror figures into a seering indictment of the British conservative establishment. Meanwhile, Revealer used broad pastiche on a micro-budget to shade the complexities of sex workers and evangelists, weaving genre tropes into an interesting piece of queer cinema.

But for me, the film that hangs heaviest over MaXXXine is one generally reviled by the horror community at large: director Edgar Wright and writer Kristy Wilson-Cairne’s smart 2021 thriller Last Night in Soho. Three years ago, Wright hit many of the same plot beats West struggles to keep compelling here. Instead of strictly drawing from giallo and horror of the ‘70s and ‘80s, however, Wright smartly chose European thrillers from the ‘60s that those directors would imitate via exploitation cinema once the film markets dried up. What he and Wilson arrived at was a dreamy, disenchanting story about the price women must pay for success, and the demons it ultimately forces them to contend with. It’s much more pragmatic, realistic film, with bold and honest assessments of misogyny that never feel cartoonish — just lived.

West essentially has made this picture again with less money and less compelling aesthetics paired with worse music, which can be forgiven — film is as referential as any art form. But I question the efficacy and need for a story like this when the conclusions it draws are ultimately self-fulfilling and self-affirming. American women succeed, the film seems to say, due to the nastiness and tenacity instilled in them by our male id. Confidence and coolness is only earned when characters like Maxine and Bender can be as violent or as perverse as the vultures circling their wagon. Protest is for squares, prudes, and people who don’t have time to work. Because work and violence is the only way to succeed, and to want to succeed is the American way.

This would almost be a compelling treatise if West was doing anything with it. But unlike Wright and Cairns, neither West nor Mia Goth have an interest in shifting the goal post. West’s last two films provide ample proof that he’s perfectly content aping easily recognizable genre film for modern audiences that lack context for what he’s referencing. Meanwhile, Mia Goth continues to stand by her aspiring Catholic priest and domestic abuser husband, Disney star Shia LeBeouf, as she soaks up accolades of being a scream queen without actually knowing what the term means.

Ah — but there it is, isn’t it? The same didactic and moralistic judgment people were so eager to heap on Marilyn Monroe back in the ‘50s and ‘60s. One of my own worst critical inclinations, too. Because this is the ultimate point of the X series, a trilogy that embraces the ugliest and worst parts of America as glamorous inevitability. Criticize it all day, but to do so with too much fervor is to play into the occasionally insightful, frequently smug wallowing that comprises much of these pictures. To pick apart this product of our culture is to pick apart the culture itself. “Society should be improved somewhat, and yet we participate in society.” Curious!

Therein lies the complicated tension of MaXXXine — both a perversion to and capitulation of Chayefsky and Freud’s theories about feminine success espoused by The Goddess. It is neither indictment nor endorsement, but simply a heightened observation. A constructed reality that only serves to highlight how lost our own truly has been for decades. And — ultimately — to own and accept our cultural evils not as vices, but as necessities to navigate the world we broke.

“So our culture is vile,” West posits, “so what?”

So what, indeed.

Notes

Not to be a problematic and reductive lesbian, but Elizabeth Debicki is gorgeous in this film. The way she carries herself, her subtle eyebrow twitches, each and every outfit — stunning. She’s become one of my favorite actresses in recent years, and this is definitely her most intentionally seductive roles to date.

I’d like to posit a theory — that nothing in MaXXXine happens. That Maxine killed her friends in X, that Pearl is her split identity’s construction of the real Pearl’s life, and that this film is Maxine’s fanciful perception of what’s really happening. That — perhaps — where this is all headed is the reveal that Maxine is the real monster here. Rewatch these with this in mind; it makes an eerie amount of sense, right?

I know I took an ad hominem potshot at Mia Goth to make larger point about the way critics can often blur reality and fiction — self included. But I want to say, for the record, that she’s up there with Debicki for me as an actress I’ve liked for a really long time. Her early turn in Cure For Wellness made me an instant fan, and I’d recommend anyone who hasn’t take a chance on that one. It’s one of the best horror pictures last decade, bar none, and Verbinski’s best picture for my money.

Share this post